|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Dublin Police and the Worker's Revolt - By Gegory Allen

|

| |

|

|

|

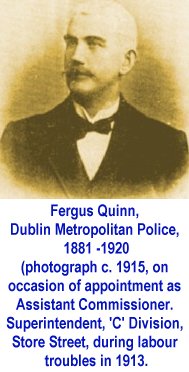

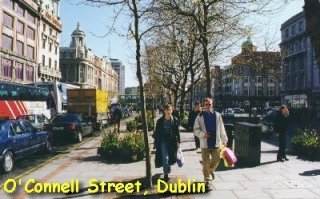

In the revolt of the workers in 1913, James Larkin was confronted in the heartland

of the conflict (Liberty Wall, Sackville Street, the North Wall) by Superintendent

Fergus Quinn of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, 'C' Division, with headquarters

in Store Street.

In the revolt of the workers in 1913, James Larkin was confronted in the heartland

of the conflict (Liberty Wall, Sackville Street, the North Wall) by Superintendent

Fergus Quinn of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, 'C' Division, with headquarters

in Store Street.

At the great demonstration in Beresford Place on August 26th, the day he called

out the tramwaymen, Larkin boasted of the rise of 'a labourer's son' to

the leadership of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. The policeman

was 'a tool of the government'. But Quinn, a native of Elphin, Co. Roscommon,

had started life as a labourer himself, and joined the DMP as a £1-a-week

constable in 1881. A self made man, he rose from the ranks to become Assistant-Commissioner,

matching the achievement of John Mallon, the great detective who solved

the Phoenix Park Murders.

Like Mallon before him, Quinn was an Irish nationalist; 'a devout Catholic Nationalist

and a man of peace', as the late District-Justice, Michael Lennon described

him in reminiscences published in 1949. In 1920 Dublin Castle, suspecting

his Nationalist sympathies forced his resignation. All his years of loyal

service were set aside. The Inspector-General of the RIC, Brigadier-Gen.

Sir J. A. Byrne, another Catholic had already been forced out, and the

same fate was also shared by Supt. Owen Brien of the 'G' Division, DMP,

and Inspector Daniel Barrett, 'B' Division, both Catholics, whose loyalty

had also apparently been called into question on account of their religion.

Like Mallon before him, Quinn was an Irish nationalist; 'a devout Catholic Nationalist

and a man of peace', as the late District-Justice, Michael Lennon described

him in reminiscences published in 1949. In 1920 Dublin Castle, suspecting

his Nationalist sympathies forced his resignation. All his years of loyal

service were set aside. The Inspector-General of the RIC, Brigadier-Gen.

Sir J. A. Byrne, another Catholic had already been forced out, and the

same fate was also shared by Supt. Owen Brien of the 'G' Division, DMP,

and Inspector Daniel Barrett, 'B' Division, both Catholics, whose loyalty

had also apparently been called into question on account of their religion.

In 1913, Quinn and his men were caught in the crossfire between the workers and

their archenemy, the employers' leader, William Martin Murphy. As his diary

shows, Quinn was at his desk early in the morning, seven days a week. There

were daily conferences in Dublin Castle in the forenoon. He inspected his

men on duty at the strike-bound premises, and supervised the nightly demonstrations

of the striking workmen who became increasingly desperate as the months

passed without hope of settlement. He was in the thick of the riots, he

remained on duty with his men long after the streets were cleared, and

was seldom in bed before one o'clock in the morning.

INCITEMENT

The Viceregal

Commission which investigated the 'disturbances' listed 30 strikes between

January and mid-August. When Larkin over-reached himself in calling out

the tramwaymen on August 26th - less than half the men answered the strike

call and the tram service was not seriously disrupted - the result was

near-anarchy, no less than 15 riots in a period of three weeks, August

30th to September 2lst.

'Speeches containing direct incitement to violence were delivered at meetings of

working men', the Commission reported in February, 1914; 'and in many of

these speeches, especially those delivered in the month of August, attacks

were made upon the police.' Some of the riots actually 'had their origin

in organised attacks on the police ... The worst element supplied by ...

cornerboys and the criminal class in the city'.

The objective analysis of the Viceregal Commission represented, in the opinion of Larkin's

biographer, his namesake, Emmet Larkin, 'a complete whitewash of the police'.

The inevitable cry of police brutality was raised many times; yet, as always

in times of social conflict, the police were more sinned against than sinning.

In one of the worst of the riots, in Great Brunswick Street on Saturday night,

August 30th, before the scenes in Sackville Street the following day provided

some grounds for the cry of provocation, an impeccable witness, Father

Michael Curran, Archbishop's House, observed the 'very severe mauling'

of half a-dozen Constables protecting trams.

The police 'behaved with singular self-restraint and in some cases with actual good

humour. 'There was an absence of violence on their part, except... when

they only employed such force as was necessary to secure and retain their

prisoners. Their behaviour was the only redeeming feature of what was for

a Dublin citizen a really humiliating and disgusting spectacle'.

In High Street on Sunday night August 3lst a mob, 600 strong, cornered two DMP

men who were rescued by another priest, Father Reilly. As they barricaded

themselves in the Presbytery, the windows were shattered by a hail of stones

and bottles.

'Unless the (police) officers in charge were prepared to abandon possession of

the streets to the rioters, they had no alternative but to give orders

to clear the various streets,' the Commission reported to the government.

TROUBLED CITY

On August 1st that year, Supt. Quinn took his leave and went abroad, possibly on

a cycling holiday in Britain: he was an enthusiastic member of the DMP

Cycling Club. On August l8th a telegram summoned him back to duty in the

troubled city. He noted in his diary: 'Returned by night mail, arriving

in Dublin by 5 a.m. having been wired to return at once to take charge

of Division owing to pending strike.' On August 2lst he himself 'wired

to Police Constables on Commissioner's leave to return off leave at once'.

By May 26th, Larkin had won control of the docks having first defeated the City

of Dublin Steamship Company, holders of the government mail contract. In

June the farmers of County Dublin, faced with the loss of the harvest,

capitulated to the agricultural labourers.

In 1911, Larkin had failed to organise the employees of the Dublin United Tramways

Company, but he was stronger now. On July l9th, Murphy called a midnight

meeting to warn the tramwaymen that he would fight Larkin; and on August

l3th repeated the warning in 'an advertisement in the press. The DUTC had

no apprehension of any trouble with their employees but (were) prepared

to meet any emergency.

The Commissioner of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, Sir John Ross of Bladensburg and his

assistant, David Harrel, had been alerted by rumour of a strike by tramwaymen,

planned for Horse Show week. On August l9th, Quinn attended a conference

in Harrel's office 'to make arrangements with other Superintendents about

strikes in the city'.

As Quinn was resuming duty that morning, Murphy closed down the Irish Independent

despatch department to forestall a strike. The following day, the newspaper

distributor, Eason, refused union demand to black the Independent and his

staff went on strike. On Thursday, Quinn recorded another blow to Larkin.

'Employees of the Parcel Department, Tramway Company, notified by Mr. Walsh

Supt. that their services were no longer required and about 120 were discharged.'

These men were each handed a notice: 'If you are not a member of the Union

when the (parcels) traffic is resumed, your application for employment

will be favourably considered.'

On August 22nd, a number of ex-Constables were sworn in for duty as gaolers in Store

Street and Fitzgibbon Street Stations. On the evidence of the diary, the

police in the 'C' Division enjoyed two relatively quiet days on Sunday

and Monday. And then, on August 26th, the Tuesday of Horse Show Week, Larkin

miscalculating his strength, called out the tramwaymen. Those who responded,

and less than half the men were members of the union, entered the fray

dramatically, abandoning the tramcars in the streets at 9.40 a.m. as the

early crowds were making their way to the showgrounds at Ballsbridge.

MONSTER MEETING

At a monster meeting in Beresford Place that night, Larkin was at his fiery

best. 'Murphy has boasted that he will beat Larkin ... a man who is going

to lead you out of bondage into the land of promise.' He had forced their

enemy 'to bow at the knee of a labourer's son.' At that great meeting on

August 26th, Larkin hurled the inevitable cry of 'police brutality'; but

he also had a word of advice for the stoic constables on duty.

If they 'were worth their salt' they would demand their rights. In 1913, the DMP

worked on average, 8 hours, seven days a week, with night duty every second

month. A constable had ten days, a sergeant 21 days annual leave. Top pay

for a constable was 30/- a week, 38/1 for sergeants, at a time when artisans

in the building trade were getting up to 36/-, unskilled labourers 18/-

for a six-day week.

Larkin scoffed at them. 'If I was doing dirty work, I would expect dirty pay.

The men who are keeping the peace are getting bad hours and meagre pay'.

In his diary for Saturday, August 23rd, Supt. Quinn had recorded a visit to Liberty

Hall to warn Larkin that the 'police could not allow (a) procession to

pass by places affected by strike'; and that night the marching strikers

were routed away from Sackville Street.

Now Larkin

invoked the example of Carson and the Ulster Volunteers. 'If they have

the right to arm, the working men have an equal right to arm.' They would

demonstrate in Sackville Street, he shouted defiantly. 'It is our street

as well as William Martin Murphy's ... we are fighting for bread and butter

and we will hold our meetings in the streets... By the living God, if they

want war they can have it.'

Now Larkin

invoked the example of Carson and the Ulster Volunteers. 'If they have

the right to arm, the working men have an equal right to arm.' They would

demonstrate in Sackville Street, he shouted defiantly. 'It is our street

as well as William Martin Murphy's ... we are fighting for bread and butter

and we will hold our meetings in the streets... By the living God, if they

want war they can have it.'

The authorities

could hardly ignore the threat. At 2.10 p.m. the next day, Quinn returned

to Liberty Hall, as the diary records: 'Warned James Larkin that no procession

of any kind would be allowed through any of the streets of the city ...

and if such, were attempted, it would be stopped by force.' The policeman

soberly recorded what must have been a heated rejoinder. '(Larkin) said

he would not be stopped by force, that police would have to accept the

responsibility and that he would at once make it known in the press and

to all Dublin'.

UNLAWFUL ASSEMBLY

Larkin made good his threat, announcing in Beresford Place that night a meeting

in Sackville Street to take place on Sunday, adding grimly that women and

children were to stay away. The rally on August 26th was also addressed

in wild language by William O'Brien, President of the Tailors' Society,

Thomas Lawlor and William Partridge, who were all arrested with Larkin

on Thursday morning. Released on bail, Larkin threw down the gauntlet:

he would be in Sackville Street on Sunday, 'dead or alive'. The government,

predictably, proclaimed the threatened demonstration as 'an unlawful assembly'.

On Friday

the 29th at 7.15 p.m., Quinn served notice of the Proclamation on Larkin

at Liberty Hall. His laconic entry for this date conveys nothing of the

ensuing drama in Beresford Place. 'In charge of police from 7.30 p.m...

Engaged at meeting outside Liberty Hall from 8 p.m.'

A crowd

of 10,000 turned up to hear James Connolly speak, and to cheer Larkin as

he burned the Proclamation. 'If they are going to stop the meeting at the

direction of William Martin Murphy, then I say that for every one of our

men that falls, two must fall on the other side... You have every right

to hold the meetings; but you have been too supine and cowardly in the

past... If the Belfast Orangemen can hold a meeting, I do not see what

is the matter that Dublin labourers can't hold a meeting, and if they want

a revolution there that day, there will be a revolution'.

On Saturday

morning, Quinn 'went to Police courts and obtained warrants for arrest

of James Larkin, James Connolly and W.P. Partridge'. In his biography,

Emmet Larkin recalls that O'Brien hurried to Liberty Hall to warn Larkin,

who succeeded in evading arrest.

MASSIVE FORCE

To prevent the meeting on Sunday, a massive force of over 300 police augmented

by members of the RIC Reserve Force was deployed on Sackville Street. At

12.40 p.m. Supt. Quinn and a force of 40 Constables were withdrawn to supervise

a meeting at Croydon Park in Fairview. The duty of arresting Larkin fell

instead to the lot of Supt. Lawrence Murphy of the 'A' Division, Kevin

Street, and Supt. Cornelius Kiernan, 'E' Division, Donnybrook. They were

close to the Imperial Hotel when Larkin made his dramatic appearance on

the balcony at 1.25 p.m., disguised as an old man, with false beard, and

a long dress coat belonging to Count Markievicz.

To prevent the meeting on Sunday, a massive force of over 300 police augmented

by members of the RIC Reserve Force was deployed on Sackville Street. At

12.40 p.m. Supt. Quinn and a force of 40 Constables were withdrawn to supervise

a meeting at Croydon Park in Fairview. The duty of arresting Larkin fell

instead to the lot of Supt. Lawrence Murphy of the 'A' Division, Kevin

Street, and Supt. Cornelius Kiernan, 'E' Division, Donnybrook. They were

close to the Imperial Hotel when Larkin made his dramatic appearance on

the balcony at 1.25 p.m., disguised as an old man, with false beard, and

a long dress coat belonging to Count Markievicz.

The trouble

started when stones were thrown by a section of the crowd. The battle-weary

police retaliated with a baton charge, the crowd fleeing into Prince's

Street where they were met head-on by another police detachment on duty

at the rear of the Independent offices. The troublemakers scattered, mingling

with innocent people coming from last Mass in the pro-Cathedral, and all

bore the brunt of the DMP onslaught.

It was

all over in two minutes, with the reputation of the DMP in ruins amid the

debris in Sackville Street, business premises and tramcars wrecked; 400

injured citizens including women and children, and 50 policemen, on their

way to the hospitals.

But who

was really to blame for the debacle; organised labour fighting for justice,

or the employers, victims themselves of inherited anti-social attitudes?

Thrust by society into no-man's land the police were the prime casualties

of peace. The Viceregal Commission offered a definitive judgement to history.

The

police had discharged their duties 'with conspicuous courage and patience.

They were exposed to great dangers and treated with great brutality and

in many instances ... though suffering from injuries which would have fully

justified their absence from duty, they remained at their posts under great

difficulties until peace had been restored. The total number of constables

injured during these riots exceeded 200.'

Copyright, 1978, Gregory Allen

Gregory Allen is a former member of the Garda Síochána and was curator

of the Garda Museum. Gill and Macmillan published his history of the Garda Síochána early in 2000.

The article was first published in the Garda Review in 1978.

It is reproduced here by kind permission of Gregory Allen (the author),

and

Andy Needham (Editor of the Garda Review).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This website is for information and recreation purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this site is true, errors and omissions are inevitable and the authors and webmaster of this site herein disclaim themselves from any responsibility.

|

|

|